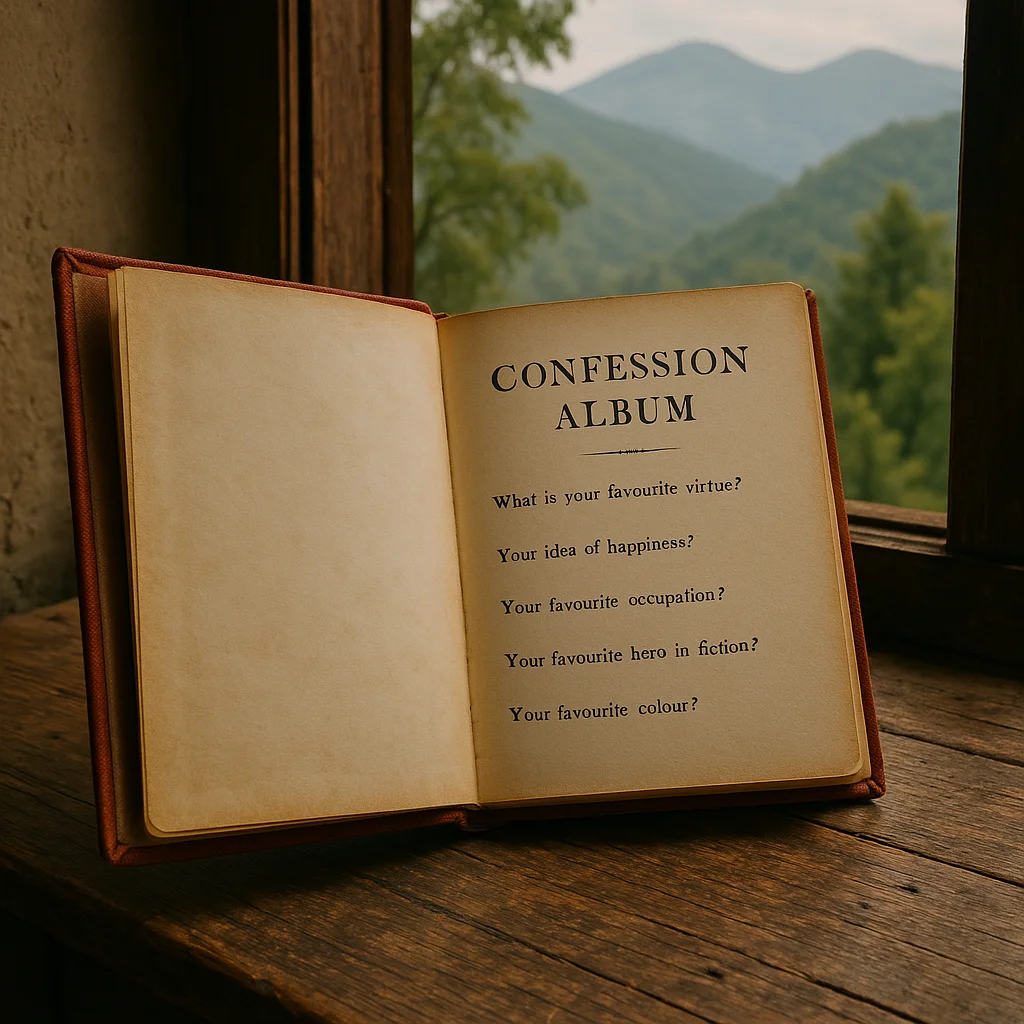

Oh, you’re in for a treat—Victorian parlor games like the “confession album” are a delightful peek into the quirky, sentimental, and sometimes surprisingly revealing social habits of the 19th century! Let’s dive into this fascinating little world.

What Was a Confession Album?

A confession album was a type of Victorian parlor game, essentially a bound notebook or pre-printed booklet filled with a series of personal, introspective questions. Think of it as a 19th-century version of those “get to know you” quizzes you might find in a modern magazine or online, but with a dash of formality and a lot more earnestness. The idea was simple: participants—often friends, family, or guests at a social gathering—would take turns answering the questions in writing, creating a keepsake of their thoughts, preferences, and personalities. These albums were part social entertainment, part memory book, and part psychological curiosity.

The Victorians adored these games because they fit perfectly into the era’s obsession with self-reflection, sentimentality, and polite socializing. Parlors were the heart of middle- and upper-class homes, where people gathered to chat, play music, or engage in light amusements after dinner. Confession albums offered a structured yet playful way to break the ice, flirt subtly, or just pass the time in an age before TV or smartphones.

Origins and Evolution

The confession album emerged in the early-to-mid-19th century, likely in Britain or France, as part of a broader trend of “album culture.” This included friendship albums (where people wrote poems or drew sketches for each other) and autograph books (for collecting signatures or witty remarks). The confession album stood out by focusing on standardized questions meant to reveal the respondent’s inner self. Its roots might trace back even further to 18th-century French “livres de confidences” or English “question-and-answer” books, but it really took off during the Victorian era (1837–1901), fueled by the rise of mass printing and a growing middle class eager for refined leisure.

By the 1860s and 1870s, you could buy pre-printed confession albums in stationery shops, complete with decorative covers and lists of questions—some editions even had spaces for multiple people to answer side by side, like a Victorian social media profile comparison. Titles like Confessions: An Album to Record Thoughts, Feelings, &c. (the one Proust answered at 13) or The Confession Album: A Book of Home Secrets popped up, marketed as both entertainment and a way to preserve personal history.

What Kinds of Questions Were Asked?

The questions varied depending on the album, but they typically blended the whimsical, the moral, and the personal. They were designed to be thought-provoking yet safe enough for polite company—though some could get surprisingly deep or cheeky. Common examples included:

- “What is your favorite virtue?” (A nod to Victorian morality.)

- “What is your greatest fault?” (A chance to feign humility.)

- “Who is your favorite poet?” (A test of cultural taste.)

- “What is your idea of perfect happiness?” (A sentimental classic.)

- “What historical figure do you most admire?” (A way to show off education.)

- Occasionally spicier ones like “What is your secret ambition?” or “Who do you love most?” (Cue blushing and giggles.)

The tone was earnest but playful, and answers could range from profound to silly. For instance, a young woman might write “To be loved” as her happiness, while a cheeky gent might list “Roast beef” as his favorite virtue. The questions weren’t fixed—each album might have 10, 20, or even 50, depending on the publisher or the host who made their own.

How Was It Played?

Picture a cozy Victorian parlor: gas lamps flickering, tea on the table, a group of friends or family in their stiff collars and crinolines. Someone—maybe the host’s daughter—pulls out the confession album. It’s passed around, and each person writes their answers, either in the moment or over a few days if it’s a house party. Sometimes it was a solo activity, with the owner collecting responses from visitors over time, like a guestbook with personality. Other times, it was read aloud for laughs or discussion, though that depended on how bold the group felt—some answers were too private to share!

The albums often became treasured mementos. Families might keep them for generations, and they’re a goldmine for historians today because they capture unfiltered voices from the past—well, as unfiltered as Victorian decorum allowed.

Why Did It Appeal to Victorians?

The confession album clicked with the era’s vibe in a few key ways:

- Sentimentality: Victorians loved preserving emotions and memories—think lockets with hair or pressed flowers. This was a written version of that.

- Self-Improvement: The period was big on moral and intellectual growth, and reflecting on virtues or faults fit right in.

- Social Bonding: It was a low-stakes way to learn about each other, especially in a society where direct personal questions could be rude.

- Romantic Undertones: For young people, it was a sneaky way to flirt—imagine a suitor spotting “You” as an answer to “Who do you admire most?” in a crush’s handwriting.

Proust and Beyond

Marcel Proust’s encounter with confession albums—first at 13 in Antoinette Faure’s book, then at 20 in another—elevated the game to literary fame. His answers (like “The need to be loved” or “My cowardice”) were so poetic and introspective that they later inspired the “Proust Questionnaire” mythos, even though he didn’t invent it. The fad peaked in the late 19th century but faded as parlor games gave way to new entertainments like board games or the phonograph in the early 20th century.

Today, you can find echoes of it in personality quizzes, icebreaker games, or even those “50 Questions to Ask Your Partner” articles. And of course, it lives on through Bernard Pivot and James Lipton, who modernized it for TV audiences.

Fun Tidbit

Some surviving albums show wild variety—answers from “Napoleon” to “My cat” for admired figures, or doodles in the margins when someone got bored. They’re a quirky mix of stiff Victorian manners and raw human quirks. If you ever stumble across one in an antique shop, it’s like holding a time capsule of someone’s soul—drool-worthy indeed!